All That Glitters Is Not Gold: Will Expectations Be Dashed in Canada's North?

Part I in a two-part series on the challenges of natural resource governance in Canada's North.

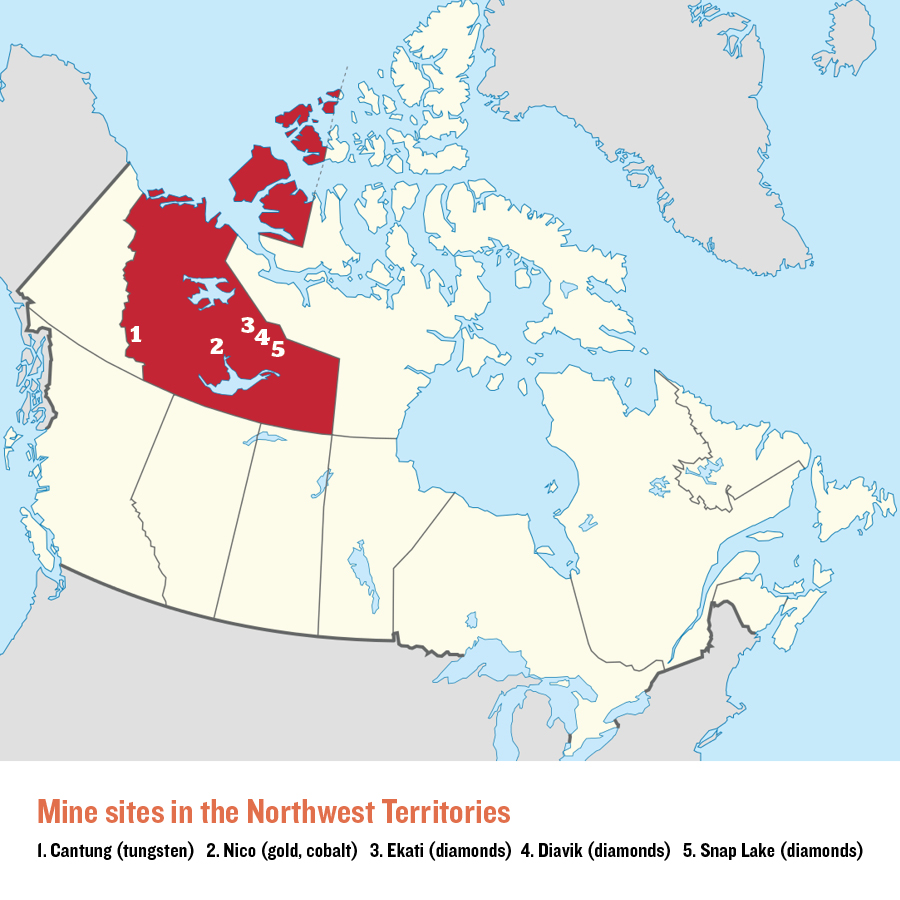

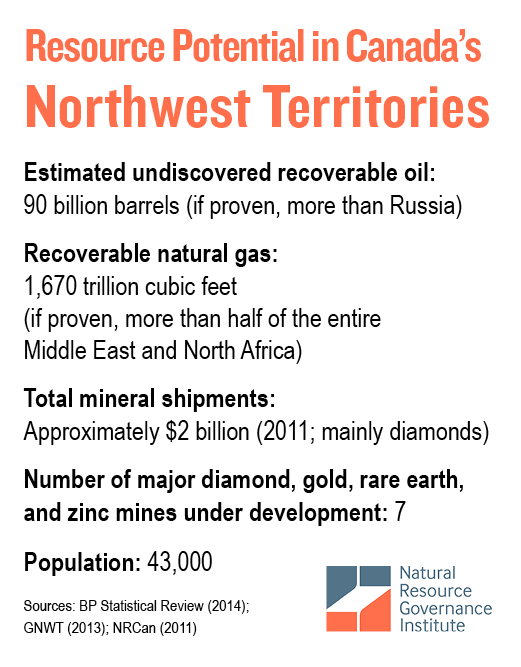

The Northwest Territories (NWT), Canada's largest territory, has huge resource potential. To investors and oil and mining companies, it is a vast landscape abundant in diamonds, gold, silver, copper, zinc, rare earth minerals, oil and natural gas (see box and map). Climate change is expected to open up even more land and sea for exploration and production. But to the government of the Northwest Territories (GNWT), these resources present an opportunity to go from mere spectators of economic development to full participants.

Until recently, almost all of the financial benefits from extraction were retained by the Canadian federal government. In 2013, things changed. The GNWT negotiated a devolution agreement allowing the territory to retain a portion of mineral and onshore oil and gas royalties, specifically the lesser of 50 percent of mineral, oil, gas and water-related revenues, or 5 percent of an amount called the "Gross Expenditure Base" (between $70-100 million per year over the coming decade). Of the amount retained by the GNWT, 25 percent is passed onto aboriginal governments that signed onto the devolution agreement. For a region traditionally dependent on the federal government for two-thirds of its revenues, the agreement was hailed as meaningful progress toward real autonomy.

"For the first time ever, NWT residents will inherit new control of the minerals industry, and with it, a significant contribution to the economic future of the NWT," wrote the government. "More money will be available for the territorial government to invest in public priorities like health care, education, housing, roads, hospitals, schools and projects that improve the life in all NWT communities.… Devolution will usher in a new era of prosperity and independence for the NWT."

Yet, despite billions' worth of proven oil, natural gas and mineral deposits in various stages of development, the government may be overly optimistic about its financial promise. To better understand why, we need to examine the mineral and oil taxation regime in Canada, as well as the intergovernmental transfer system between the federal and territorial governments.

All that glitters is not gold

Oil and mining companies operating in the NWT currently make two types of tax payments, royalties and corporate income taxes. All royalty payments are made to the federal government except where land has been specially designated "reserve land" held in trust for aboriginal bands. The size of the royalty ranges from 5 to 14 percent of profits on mineral extraction, depending on the size of earnings. For oil and natural gas, it ranges from 1 to 5 percent of gross revenues, growing over time.

Under the devolution agreement, the GNWT will receive less than $100 million more per year from the royalty amount—less than $60 million per year in the near future as the Diavik and Ekati mines slow production—a modest windfall for a government with a $1.5 billion budget.

Oil, natural gas and minerals are also subject to corporate income taxes. A 15 percent corporate income tax is paid to the federal government while an 11.5 percent corporate income tax is paid to the GNWT. The same rates apply to oil, gas and minerals.

In theory, if the boom in oil, gas and mineral production goes as planned, the GNWT could collect significant corporate income tax windfalls. Alas, there are two reasons to doubt this will happen.

Leaks in the revenue pipeline

First, Canada has one of most generous mineral taxation incentive schemes in the world. In 2011, less than $100 million was collected in royalties on NWT exports worth over $2 billion (exact figures are unavailable).

Second, even if the GNWT does collect significant corporate income tax revenue, there is another reason the territory would not benefit fully from the windfall. Under the Territorial Financing Formula (TFF), the formula that determines the annual unconditional transfer from the Government of Canada to the GNWT, for each dollar the territory raises itself in taxes, approximately 70 cents are removed from the federal transfer. In other words, even if corporate income taxes rose significantly, much of the revenue would be clawed back.

An argument can be made that the GNWT might benefit financially from a mining or oil boom through other channels. A major influx of oil field or mine workers could boost personal income and property tax collection, for instance. More money would also be transferred from the federal government for each new resident under the Territorial Financing Formula. However increases in these sources of revenue may also be marginal since only about half of miners currently working in the NWT officially reside in the territory, a trend that is likely to continue.

In most countries the largest benefits from natural resource extraction are the fiscal benefits from royalties and taxes, even at the local level. Unless the territory introduces new royalties or taxes, the revenue sharing scheme between the NWT and the federal government is renegotiated, or the Canadian government closes some of its tax loopholes, the NWT may be disappointed by the paltry fiscal benefits the coming oil and mining boom will bring.

Andrew Bauer is an economic analyst at NRGI. In his second blog post, he shares what the NWT has learned from resource revenue management of other countries and details NRGI's work to help the territory transform its mineral wealth into well-being for citizens.