Aramco’s Billions Hint at Hidden State Oil Riches Worldwide

Note: This post relates to the upcoming 25 April launch of NRGI’s National Oil Company Database. Register to attend the Washington, D.C. launch event.

Last week, investors and Saudi Arabia watchers got an eyeful of the massive riches of state oil company Saudi Aramco, which in a prospectus reported USD 111 billion in profits for 2018. That Aramco is minted surprises no one; but the sheer scale of its horde was indeed headline-worthy.

Saudi Arabia is one of 25 economies that we at NRGI have found to be “NOC-dependent”—not just oil-dependent, but specifically dependent on their own national oil companies, many of which are dangerously regarded as “too big to fail.” Research that we’ll launch in the coming weeks shows that the rules on how much revenue these companies hand over to their governments in taxes and other transfers—and the incentives they have to spend efficiently—have a massive influence on how governments’ execute their core functions.

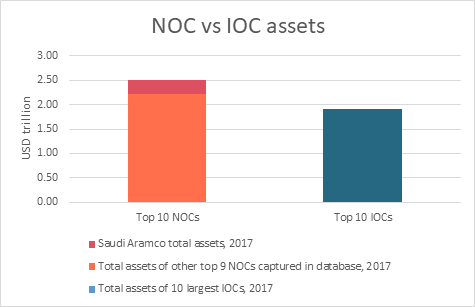

In fact, while international oil companies often grab the headlines with their corporate derring-do and executive pay (as well as climate change chicanery and corruption scandals), it is actually national oil companies which are the biggest and arguably most influential players. We have been assembling a database from the public reporting of NOCs across the world; the total 2017 assets of the top 10 NOCs that publish this data – now including Saudi Aramco – tower over the assets of their private sector brethren by a margin of about thirty percent.

Despite their role as custodians of masses of public money, state oil companies are notoriously opaque—something that Aramco is now trying to change as it woos bond markets. Missing from the chart above are the assets of several NOCs that rank among the world’s largest oil producers but still do not publish basic financial data. The lack of transparency is problematic for more than just investors, since many such companies operate in countries where citizens are materially much worse off than the average Saudi—and where public funds for social spending are desperately needed.

Aramco and its auditors note in the prospectus that the company faces persistent risks from volatile international oil prices. While few countries are as oil-dependent as Saudi Arabia, most NOCs don’t have the same cushion that Aramco has during price downturns—so while the kingdom’s vast oil reserves have enabled the company to thrive with relatively little debt, many other NOCs are significantly indebted. Some have required costly bail-outs, meaning that instead of being engines for national development they have become drains on public finance.

In light of their importance, and the risks associated with them, strong oversight of NOCs is critical. Governments and NOCs must deepen commitments to transparency. State companies such as Colombia’s Ecopetrol and Malaysia’s Petronas have shown the ability to lead and institute robust reporting systems even amidst broader governance challenges. Yet in some countries, NOC executives and government officials view thorough and consistent reporting as a burden. In fact, transparent reporting is among the most important tools for building public trust and the development of a performance culture. Consistent reporting on its own is not enough to square the vast oil wealth managed by NOCs with the poverty that persists in many countries, but it is an important step in that direction.

Patrick Heller is an advisor with the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).

Authors

Patrick Heller

Chief Program Officer