Five Questions About How Debt Relief Initiatives Will Work for Resource-Rich Countries

中文 »

The world’s poorest nations face enormous challenges as they seek to contain the coronavirus pandemic amid a severe global economic downturn. Resource-rich countries are especially hard hit as a result of the plunge in the prices of oil prices and many key minerals. In response to widespread calls for support, the G20 nations offered temporary debt service suspension to 73 countries, and an important group of private sector lenders also indicated willingness to extend temporary support. But so far little actual debt relief has materialized.

The success of these global efforts seems to hinge on key lenders’ willingness to participate on equal terms. Most of them don’t want to extend financial help to countries that will then use the funds to repay less generous lenders. The World Bank’s newly appointed chief economist has questioned whether China was fully committed to debt relief, while the bank’s president has expressed frustration about private sector participation so far. Given this uncertainty, it is unsurprising that officials in some countries, such as the Kyrgyz Republic, have chosen a bilateral route, renegotiating debt directly with China. Kenya’s finance minister also said he will seek to renegotiate bilaterally with only select state creditors so as not to risk the country’s reputation with private creditors.

At NRGI, we recently studied resource-backed loans (RBLs) in a variety of resource-rich countries; that work informs a few questions pertaining to recent debt relief efforts. RBLs are a special form of government debt repaid using natural resource wealth. They matter because they are a significant part of overall debt in a number of countries and also because they illustrate the complex scope of debt renegotiations. The answers to these questions appear mostly unknown or in the works, but they will ultimately have a significant impact on how much help these efforts can bring to resource-rich developing countries as they manage the crisis.

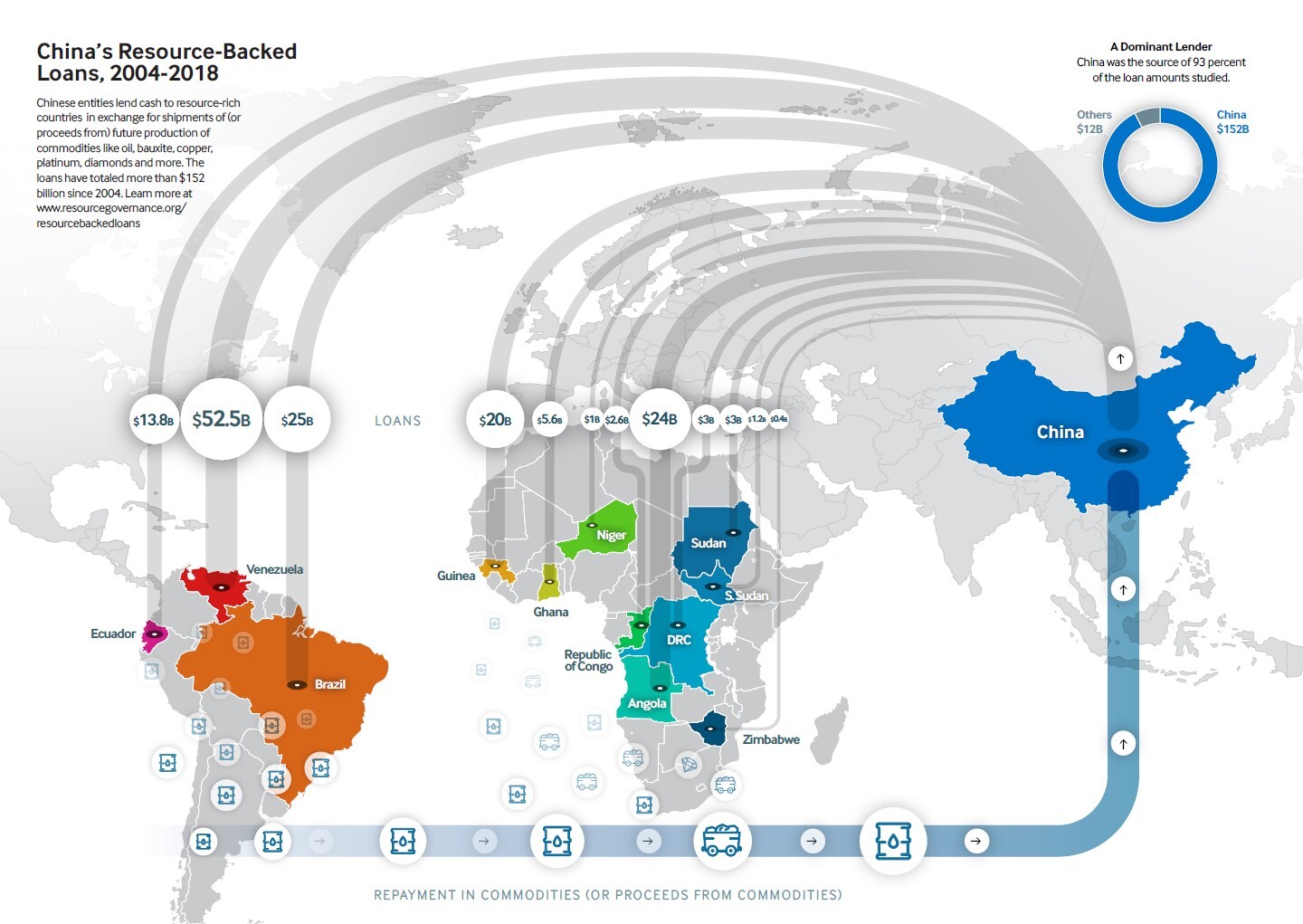

Will debt relief initiatives cover Chinese resource-backed loans?

China is one of the key lenders to developing countries. Our research confirms this finding for the subset of loans that are resource-backed. Chinese entities accounted for $152 billion (more than 90 percent) of the total amount lent through RBLs between 2004 and 2018. For example, Guinea’s government signed an enormous $20 billion (double the country’s GDP) RBL agreement in 2017 with Chinese state companies, which it is starting to draw down to build roads and other infrastructure. This is why China’s participation in the G20 initiative was initially seen as such a big feat. But there are worrying signs that not all loans from China may be covered.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

Source: Resource Backed Loans: Pitfalls and Potential

In a recent article, a senior official at Chinese think tank associated with the Ministry of Commerce suggests that the authorities in Beijing may differentiate between “interest-free” inter-governmental loans, which are applicable for debt relief, and “preferential loans with commercial character,” such as those provided by China Eximbank (a major RBL lender). He writes of the latter that “due to the commercial character of projects behind preferential loans, [they have] never been applicable for debt relief.”

Various Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs), including China Eximbank, typically provide RBLs at lower-than-commercial rates and are repaid by proceeds from designated oil or mining projects. Should the Chinese think tank official’s view carry the day, Chinese RBLs may not be eligible for debt relief, despite the fact that borrower countries have used them in large part to build public infrastructure, such as roads and hydro dams, similarly to other loans.

Luckily Guinea’s recent RBL, to be repaid using proceeds from bauxite mining, is currently under a grace period with repayment only to start in 2022. But Guinean officials will surely have one eye on the calendar and the other on aluminum prices, watching what happens to countries that miss a payment.

Will debt relief initiatives cover loans from commodity traders?

The landscape of creditors lending to developing countries has grown increasingly complex—hence the (at least nominal) willingness of a body representing a large group of private investors (IIF) to participate in debt relief efforts. Their participation is significant, even if it is only on a case-by-case basis. But there is a risk that one group of lenders, not members of IIF, may fly under the radar.

Research by NRGI and Global Witness has shown that commodity traders are key lenders to governments in several poor countries including Chad, Congo and South Sudan. Trader loans are also to be repaid from resource proceeds, and often feature high fees and interest rates. Companies may label these loans as short-term advances or “trade finance,” even though many feature multi-year maturities and have been syndicated to (funded by) banks. They also appear to be missing from international debt statistics.

Some trader-provided RBLs have already been renegotiated. In 2018 Chad negotiated lengthened maturities and lowered interest rates with Glencore, a major trading firm. The recent deal concluded between trading firms and Congo led to a 30 percent discount (“haircut”) on some debt, as well as a deferral of four months on the repayment which is now scheduled to start in October 2020. Angola is also renegotiating its debt with Chinese traders Sinopec and Sinochem. But South Sudan is still using a hefty part of its shrinking oil revenue to service loans to various commodity trading companies. Even with adjusted terms, oil-dependent countries such as these will struggle to repay the loans in the current context. Given the size of their loans and the dire straits in which their borrowers find themselves, commodity traders should also join the global debt relief effort.

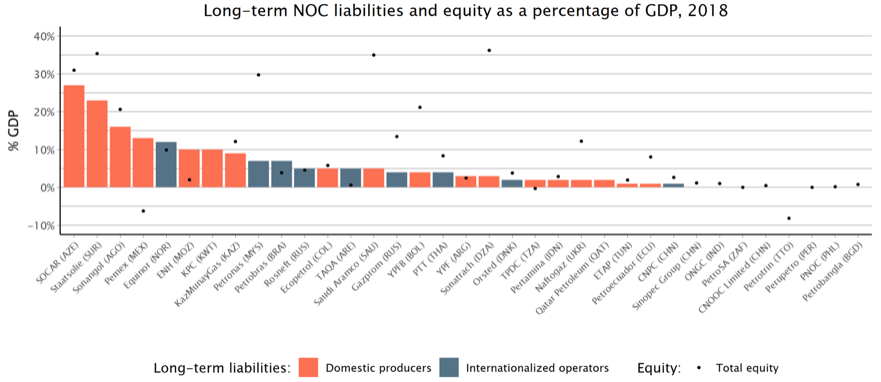

What will happen to state-owned enterprises’ debt?

The calls for temporary debt relief are focused on official government debt. But in a number of resource-rich countries (e.g., Angola, Mozambique), national oil companies and other state-owned enterprises carry huge chunks of the overall external public debt. In the Republic of Congo, where undisclosed debt led to major debt problems in 2015, recent reporting reveals large liabilities on the national oil company’s books are missing from official statistics.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

Source: National Oil Company database, NRGI

Some mineral-rich countries in Africa, such as Ghana and the Democratic Republic of Congo, have gone even further establishing elaborate financial structures to borrow using joint-venture firms owned by both state companies and foreign (Chinese) investors. The debt accrued through DRC’s Sicomine deal on its own represents about half of DRC’s total external debt. Some SOE loans come with explicit government guarantees, but even when there aren’t any, it seems unlikely that the government would let these giant state companies go under in the event of a default on payments.

Exactly which state borrowing current debt relief proposals will cover is unclear, as there are good reasons to exclude loans for commercial activities. In a recent document IIF stipulated that its members don’t foresee SOE loans being covered under a possible deal. But it this is an important moment for reckoning in the dangers of borrowing off the books when the SOE is actually carrying quasi-fiscal activities instead of the government.

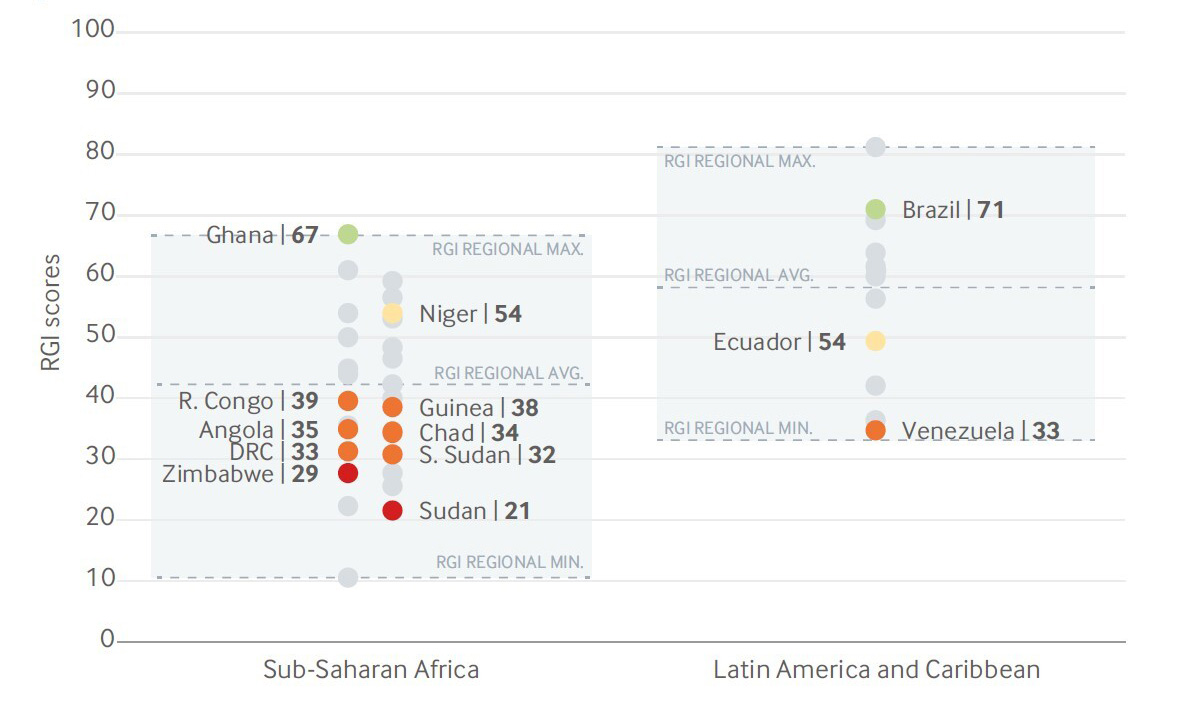

Will debt relief initiatives sufficiently account for corruption risks and transparency?

Civil society organizations could play a critical role in calling for participation of key actors in debt relief, but in many places there is no information about who those actors are. Debt statistics from the World Bank and other sources rarely disaggregate loan data beyond broad categories (e.g., private, official, multilateral), and typically provide no information on how much is due in future years. Certain loans, including those from traders and Chinese entities (as discussed above), are often missing entirely from global debt datasets.

Knowing the repayment terms of loans is also critical. Some RBLs require repayments fixed in volume terms, others in market value terms—an important distinction when the value of commodities can be so volatile. Some borrowers may pledge assets (including resource reserves) as collateral. Our own study revealed that only in 1 of 52 instances did state borrowers or the lender make a RBL contract public, which makes it impossible to know which loans present the greatest risk.

The G20 relief initiative stipulates that borrower countries’ participation is contingent on coming clean on how much they owe in total. Though details are open to interpretation, a commitment to disclosing all public debt is really a bare minimum first step to be expected from all countries receiving any concessional loans. Any debt relief should instead be conditional on full transparency (as stressed by IIF and EITI), including around the servicing due and creditor terms and conditions. The G7 went further, explicitly urging transparency of collateralized loans and SOE debt, and warning against use of confidentiality clauses—a thinly veiled swipe at China’s resource backed loans.

As we revealed in our RBL report, the most significant borrowers include countries with weak governance and concerning records of corruption. Where poor governance and corruption risks run high, debt relief may not translate into quality spending on social welfare or economic development.

Resource Governance Index scores of resource-backed loan borrowers

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

Source: Resource Backed Loans: Pitfalls and Potential

Lenders will face tough questions about how to respond to this challenge. For instance, nearly 100 NGOs called upon the International Monetary Fund to prioritize anticorruption measures in its emergency financing response and support civil society’s ability to monitor the use of these funds. Partly in response to such pressure, the IMF is adopting measures to advance the transparent and accountable use of the new loans. But in some country contexts, these limited measures won’t be enough to safeguard funds from abuse.

In addition, debt renegotiations, particularly if they end up being largely bilateral, risk bringing more questionable and opaque deals.

While hardly a panacea, transparency offers one potential safeguard that a wide set of lenders could practically adopt to boost accountability around debt negotiations and flows of funds. Given the severity of the crisis, this is the right time to ramp up reporting, including on RBLs.

Will short-term debt relief suffice to get out of the current crisis?

Economists are hoping for a rapid “V-shaped” global economic recovery from this crisis. If this materializes, temporary debt relief in the form of debt service suspension of the type initiated by the G20 (which defers debt repayment obligation due in the remainder of 2020) or the bilateral debt rescheduling generally favored by Beijing may provide the critical breathing room some countries will need to combat the epidemic in the coming months. Recognizing the risk of a prolonged crisis, there have recently been calls to extend debt suspension for another year or up to three years.

But oil-dependent developing countries are facing a different challenge altogether. Many of them struggled when oil prices dropped from well above $100 per barrel to the $50-$70 per barrel range in the 2015-2017 period. Then Angola and Venezuela requested from Chinese creditors a temporary easing of loan conditions, while Chad and the Republic of Congo renegotiated their loans with commodity traders. Many more oil-rich developing countries had already lined up for IMF loans to help balance their books before the pandemic.

Now oil is below $40 per barrel and may well stay low for a long time. In that case temporary debt service suspension or rescheduling is likely to provide only limited help to oil producers and will mostly just help them to kick problems further down the road.

Many of these countries are likely to need serious debt restructuring (reducing the amounts to be repaid), rather than just rescheduling their loans (delaying repayment deadlines). These will need to be coupled with governance reforms aimed at ensuring that resource wealth is not squandered, and structural economic reform to reduce their overall dependence on the sector.

David Mihalyi is a senior economic analyst with the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).