A Formidable Coalition: Activists, Journalists and Parliamentarians Come Together in Cameroon

Greetings from the first of two weeks of the summer school course that the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) organizes annually in Yaoundé, Cameroon, in partnership with the Catholic University of Central Africa.

This comprehensive course, now in its fourth edition, is offered under NRGI’s regional knowledge hubs program and is the flagship offering of the francophone Africa hub (Centre d’Excellence sur la Gouvernance des Industries Extractives, or CEGIAF). It is taught in French and, over two weeks, covers key issues in the governance of oil and gas, such as the discovery of resources, the decision to extract, contracts, tax regimes, social and environmental issues, and management of resource revenues. This year the course welcomes 32 delegates from civil society, parliaments and media involved in the oversight of oil, gas and minerals from ten French-speaking countries in central and western Africa.

Multiple stakeholders multiply impacts

For the first time, we have members of parliament (MPs) from Guinea, Burkina Faso and the Democratic Republic of Congo joining the course. It is also the first time we have mixed MPs with civil society actors and journalists, and in a region where there is very low level of trust in decision makers. We worried that this could turn out to be a combustible mixture, but have been delighted to learn that our fears were unfounded. Participants appreciate the roles that other types of actors play, and are understanding of the constraints unique to each. For instance, a CSO representative complained that parliaments never or rarely use their sanction power, leading to an informative debate on the issue. An MP clarified that this power is both “narrow,” limited to votes of no confidence, and “extreme,” because it leads to a government’s demise. It is a power that should be used in exceptional cases but is also one that, given its effect, is subject to political constraints. Other than using censure motions, parliaments can generally only make recommendations, and ask questions, hoping that the executive will act on them.

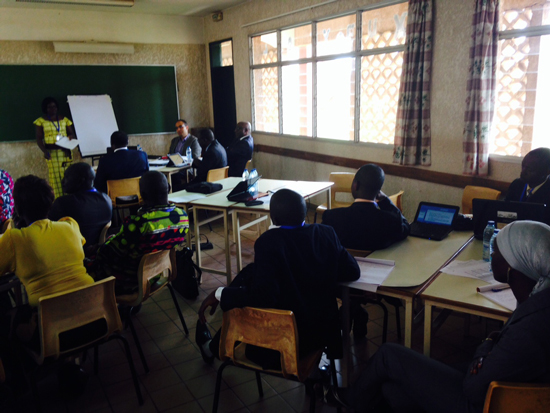

Getting to know each other: MPs (top right), journalists (bottom right) and civil society actors (left) discuss their respective roles.

Beyond promoting mutual understanding, the debate underscored common challenges around which heterogeneous coalitions can work for greater impact—lack of access to information, for example. Finally, the debate pointed to complementarities and synergies between these groups. One MP noted how he used question time in parliament to shed light on allegations, first raised in a civil society analysis, that a contractor was breaking cost allowance rules and inflating its costs.

A knowledgeable movement

What we’re seeing this week inspires confidence in the state of the extractive industries governance movement in the region. Let me explain using one issue that has come up in the course: the importance of setting a long-term strategy to convert natural resources into tangible benefits for citizens. Most participants indicated that their countries lack an adequate strategy for resource extraction. Even where national development plans exist, they make little-to-no mention of extractive industries. Also, the drafting of these plans is often driven by international institutions, with scant national leadership and inconsistent participation of key societal forces in the drafting process. Furthermore, there is little political willingness to abide by these plans once they are drafted.

One MP from Guinea pointed out that laws and policies contain general principles in relation to how resources are meant to benefit the country. A peer from DRC countered that the principles contained in laws are often so general and vague that they cannot be monitored. One civil society participant then suggested that any strategy for sector development should be clearly linked to the national development plan, and include realistic and measurable targets. Countries also need a framework to monitor progress, the activist added. In this respect, the session facilitator stressed the importance of equipping institutions with the mandate to translate strategy into concrete actions. This requires competent staff and financial resources. In a ten-minute discussion, participants serendipitously replicated the key recommendations contained in precepts 1 (on strategy and institutions) and 2 (transparency and accountability) of the Natural Resource Charter.

This level of dialogue would have been unthinkable a decade ago. Back in 2005, when I attended my first training on oil and gas for civil society in francophone Africa, most of the debates were infused by a sense of civil society’s frustration with government; hesitation to speak freely on politically sensitive topics for fear of retaliation; and a widespread dearth of technical knowledge of the sector. Almost ten years on, civil society has grown into a mature and informed force for reform.

In francophone Africa, more sophisticated civil society players, increasingly open-minded parliamentarians, and journalists conversant in the issues together seek improvement in the governance of natural resources—and thereby the wellbeing of citizens. And I’m happy to report that they are now better positioned than their predecessors to accomplish meaningful change.

Francophone Africa hub trainings are supported in part by French Cooperation and Misereor.

Matteo Pellegrini is NRGI’s head of capacity development.