IMF Optimism and Oil-Dependent Countries: Be Wary of Sunny Projections

Countries that are net exporters of oil and gas are experiencing an unprecedented twin attack: a global economic contraction driven by the coronavirus pandemic and the biggest single negative oil price shock in modern history.

Oil prices have plunged 60 percent on average since early January, a result of plummeting demand, a growth in supply and a lack of storage capacity. It is uncertain whether prices will rebound.

Some analysts claim that a supply crunch will lead to a swift recovery in 2021. The overall consensus is more conservative, suggesting that prices will remain muted for an extended period despite the recent OPEC+ deal.

Oil companies are already cutting planned investments, some high-cost fields are no longer viable, and revenues from low-cost fields are squeezed. In some countries, oil production may never again reach pre-crisis levels due to technological “shut-ins.”

“Vastly over optimistic”

Last week, the International Monetary Fund released its latest forecasts for the global economy. While headlines described the IMF’s outlook as “grim,” we believe the growth projections are still vastly over optimistic, especially for oil-dependent countries.

The IMF projects that the economy of Algeria, with high debt levels and a nearly empty sovereign wealth fund that was valued at more than $70 billion just seven years ago, to contract by 5.2% this year and grow by a miraculous 6.2% in 2021.

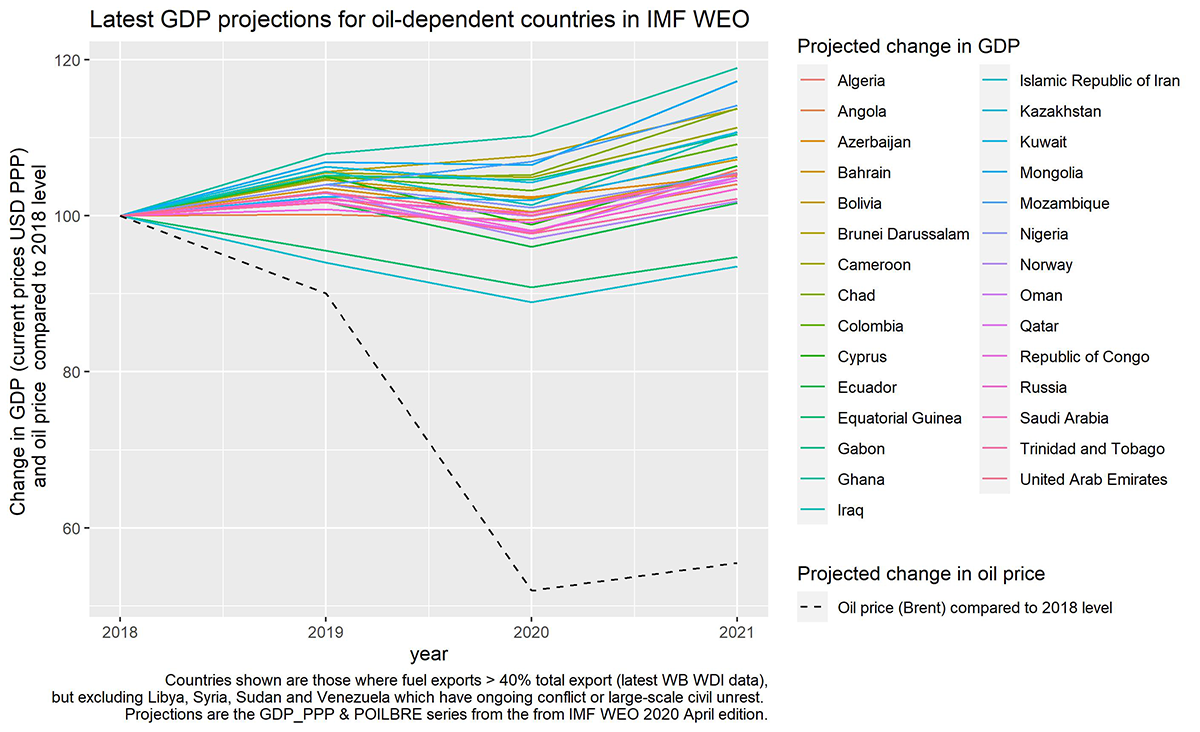

Chad’s economy—where about half of government revenues and 90% of exports come from the oil sector—is projected to shrink by just over 0.2% this year and grow by 6.1% in 2021. The IMF projects similar trends for almost all oil-dependent countries and those in Africa are no exception (See chart).

Our previous research demonstrates that the IMF systematically over-estimates the impact of oil and gas discoveries on economic growth. In many developing countries, turning oil and gas wealth into tangible benefits is tricky, with projects often stalling, companies regularly avoiding taxes, and officials sometimes mismanaging funds.

Oil-dependent countries not on similar recoveries

The IMF’s assumptions that containment measures will be lifted in most countries by July and that countries will lose between 13 and 21 working days in the second quarter of 2020 may be optimistic. Even if they are correct and diversified economies experience a rapid economic rebound after lockdowns end, officials in oil-dependent countries should not bet on similar recoveries.

The reasons for this are largely included in the IMF’s own report; its analysts assume that oil prices will stay low, with the Brent price at $37 in 2020, and $39 in 2021. The report also shows wide fiscal and trade deficits for most resource-rich countries over the next two years, but nevertheless suggests that growth will rebound impressively in 2021.

We believe that such sunny projections are not just misleading but dangerous. First, given the long-term impacts of the dual shock, some highly indebted oil-rich countries will become effectively insolvent. Standard and Poor’s downgraded Angola and Nigeria’s sovereign debt ratings; several other countries are likely to follow. A temporary moratorium on debt servicing only pushes the problem down the road.

The IMF’s optimistic scenarios may convince some officials to borrow with the intention of spending to outlast the crisis. But many high-cost producers, such as Angola and Nigeria, should expect a long-term decline in GDP rather than a temporary dip, due to shelving of new projects and permanent shut-downs of high-cost fields. They will not be able to sustainably spend their way out of the crisis. Counting on an oil recovery that may never emerge would not only impair post-crisis recoveries, but would also delay essential reforms, namely diversification of economies heretofore dependent on oil.

Fast recovery expectations

Second, the IMF’s optimistic outlook raises expectations of a fast recovery. If this hope proves unfounded, citizens’ frustrations are likely to grow, fuelling populism and public backlash at politicians and international bodies.

Third, overly optimistic modeling can also prompt governments to support oil and gas projects that are unviable at lower prices. Public and private oil companies in several countries have requested large bailouts or tax relief, appealing for emergency support during a “temporary” crisis.

Government officials must consider the risks of throwing good money after bad, especially given the enduring climate challenge and the need to shift to renewable energy.

Governments ought to resist hasty demands and properly evaluate (and model) the viability of projects at lower prices. If an oil company is facing insolvency, a bailout is not necessarily the answer. Governments could seek new investors or let companies return licenses to the state.

Better approach

Rosy projections might be driven by the IMF’s own lending policies in the short term. These require countries to carry “sustainable” debt burdens to access newly available emergency funds (or carry on with existing lending programs such as in Angola, Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea).

But a better approach would be for the IMF to change its lending criteria to allow for emergency loans and grants even in countries in unsustainable debt positions. The IMF can also support insolvent countries by establishing a sovereign debt restructuring facility that coordinates negotiations and removes obstacles to timely, orderly restructuring.

Bottom line: Many emerging country governments rely on IMF forecasts. The predictions set expectations and bilateral donors rely on them as an indicator of public sector solvency. The IMF should revisit these projections over the next quarter, “speaking truth to power,” as it is meant to.