Making Natural Resource Revenue Sharing Work

The full NRGI-UNDP report is available here.

Despite a peace agreement signed last year, Libya remains embroiled in violent conflict. At the heart of the conflict is oil, which accounts for more than 90 percent of government revenue. The vast majority is produced in the country’s east and south though the commercial and administrative capital, Tripoli, is in the west. Just like in other parts of the world suffering from natural resource-fueled conflicts—including Myanmar’s Kachin state and India’s Jharkhand—disagreements over how national and subnational authorities should share non-renewable resource revenues are threatening the nation’s stability and future.

Natural resource revenue sharing—the legal right of different regions to either directly collect some taxes from oil or mining companies or for the central government to distribute resource revenues to different regions according to a formula—has been proposed as one of the means of ending the Libyan war.

Beyond their potential for bringing peace, revenue sharing systems can compensate producing regions for environmental damage and loss of livelihoods associated with oil, gas and mineral extraction. They can also serve as an acknowledgement of local claims over resource wealth, even in regions without conflict. This approach has been used in Indonesia’s Aceh region, Papua New Guinea’s Bougainville region and Nigeria’s Niger Delta to defuse resource-fueled civil wars, reduce poverty and promote economic development in resource-rich regions, with a degree of success in each.

However, global experience shows that resource revenue sharing is not a panacea in countries where natural resources and conflict coincide. In a new study, the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) explore 30 cases of resource revenue sharing and find that many of these systems suffer from flaws in design and implementation.

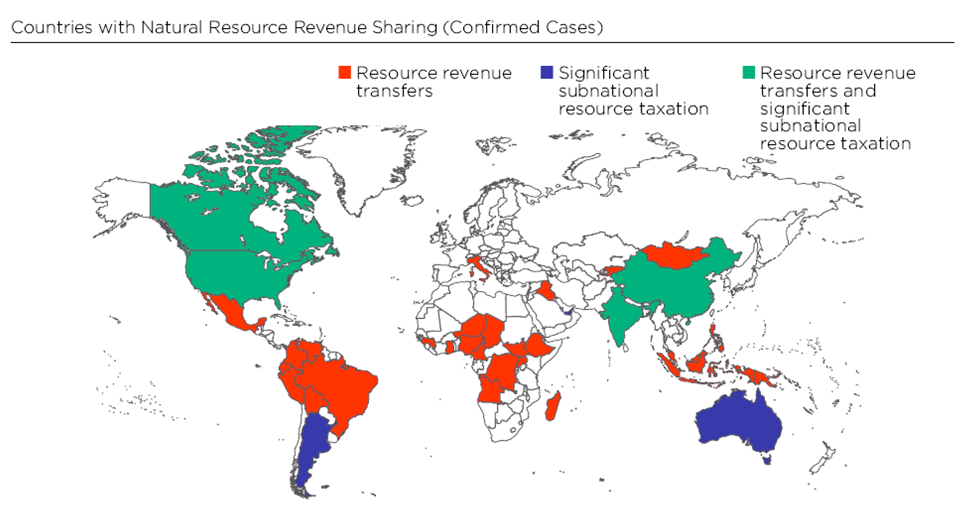

In particular, derivation-based systems—where a large portion of resource taxes are either collected directly by subnational governments or transferred by national governments back to their area of origin—intensify boom-bust cycles at the local level. These systems undermine some key principles of sound financial management, such as matching local government revenues with the cost of their regulatory, social service and infrastructure responsibilities. As such, resource revenue sharing systems often lead local governments to over-spend on conspicuous infrastructure projects such as fountains and ostentatious government buildings, and under-invest in healthcare and education. Derivation-based systems are the most common type of resource revenue sharing, as the map below shows.

Worse, in some cases these systems can actually exacerbate violent conflict. Poorly designed systems can incentivize groups to seize control of extractive sites to access a higher share of revenues, as in Peru from 2005 to 2008. Local leaders can then use these revenues to finance violence. Other problems relate to inadequate transparency and oversight or the failure of national governments to make fiscal transfers according to the agreed formula.

While NRGI and UNDP do not advise countries to simply adopt other countries’ systems, we do advise learning from their experiences and “mixing and matching” elements that work well in similar situations. In our report we offer 10 recommendations, mindful that each country is unique. Among these recommendations is that national and local leaders:

While the urgency of agreeing on a revenue sharing formula has lessened since commodity prices fell in 2014 and 2015, the issue remains important. Commodity prices are already starting to rise, and new systems or reforms are being proposed, not just in Libya but also in Kenya, Indonesia and elsewhere. Should Libya adopt a resource revenue sharing system, policymakers would be wise to heed the lessons of other countries—both the successes and failures.

Andrew Bauer is a senior economic analyst at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI). Uyanga Gankhuyag is an economist at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Sofi Halling is a policy analyst at UNDP.

Despite a peace agreement signed last year, Libya remains embroiled in violent conflict. At the heart of the conflict is oil, which accounts for more than 90 percent of government revenue. The vast majority is produced in the country’s east and south though the commercial and administrative capital, Tripoli, is in the west. Just like in other parts of the world suffering from natural resource-fueled conflicts—including Myanmar’s Kachin state and India’s Jharkhand—disagreements over how national and subnational authorities should share non-renewable resource revenues are threatening the nation’s stability and future.

Natural resource revenue sharing—the legal right of different regions to either directly collect some taxes from oil or mining companies or for the central government to distribute resource revenues to different regions according to a formula—has been proposed as one of the means of ending the Libyan war.

Beyond their potential for bringing peace, revenue sharing systems can compensate producing regions for environmental damage and loss of livelihoods associated with oil, gas and mineral extraction. They can also serve as an acknowledgement of local claims over resource wealth, even in regions without conflict. This approach has been used in Indonesia’s Aceh region, Papua New Guinea’s Bougainville region and Nigeria’s Niger Delta to defuse resource-fueled civil wars, reduce poverty and promote economic development in resource-rich regions, with a degree of success in each.

However, global experience shows that resource revenue sharing is not a panacea in countries where natural resources and conflict coincide. In a new study, the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) explore 30 cases of resource revenue sharing and find that many of these systems suffer from flaws in design and implementation.

In particular, derivation-based systems—where a large portion of resource taxes are either collected directly by subnational governments or transferred by national governments back to their area of origin—intensify boom-bust cycles at the local level. These systems undermine some key principles of sound financial management, such as matching local government revenues with the cost of their regulatory, social service and infrastructure responsibilities. As such, resource revenue sharing systems often lead local governments to over-spend on conspicuous infrastructure projects such as fountains and ostentatious government buildings, and under-invest in healthcare and education. Derivation-based systems are the most common type of resource revenue sharing, as the map below shows.

Worse, in some cases these systems can actually exacerbate violent conflict. Poorly designed systems can incentivize groups to seize control of extractive sites to access a higher share of revenues, as in Peru from 2005 to 2008. Local leaders can then use these revenues to finance violence. Other problems relate to inadequate transparency and oversight or the failure of national governments to make fiscal transfers according to the agreed formula.

While NRGI and UNDP do not advise countries to simply adopt other countries’ systems, we do advise learning from their experiences and “mixing and matching” elements that work well in similar situations. In our report we offer 10 recommendations, mindful that each country is unique. Among these recommendations is that national and local leaders:

- explicitly define the objectives of their natural resource revenue sharing systems

- select the types of taxes and revenues to share based on ease of collection and verification

- keep local governments’ expenditure responsibilities in mind when designing their system

- achieve a national consensus on the formula for revenue sharing

While the urgency of agreeing on a revenue sharing formula has lessened since commodity prices fell in 2014 and 2015, the issue remains important. Commodity prices are already starting to rise, and new systems or reforms are being proposed, not just in Libya but also in Kenya, Indonesia and elsewhere. Should Libya adopt a resource revenue sharing system, policymakers would be wise to heed the lessons of other countries—both the successes and failures.

Andrew Bauer is a senior economic analyst at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI). Uyanga Gankhuyag is an economist at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Sofi Halling is a policy analyst at UNDP.