Zambia Votes for President, But What Will the Winner Do About Copper?

Zambians are at the polls today to choose the next president of their copper-rich country. A principal election issue has been how the country taxes its mining industry. In December, parliament passed a 2015 budget that dramatically reforms the country's mining tax code, and the table below describes these changes, along with some historical data.

In essence the reform throws out the previous structure of corporate income tax on unrefined copper production, as well as the variable profit tax, which was designed to give the government a greater share of benefits in the event of windfall profits for companies. In place of these instruments, the reforms increased the royalty rate from 6 percent to 8 percent for underground mines (such as Glencore-owned Mopani) and 20 percent for open-pit mines (such as Kansanshi, owned by First Quantum). The difference in royalty rates reflects the fact that open-pit mining is typically less costly than underground mining.

|

Year |

2001 |

2008 |

2009 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

|

Average copper price |

1,580 |

6,963 |

5,165 |

7,959 |

7,331 |

6,863 |

? |

|

Mineral royalty |

0.6% |

3% |

3% |

6% |

6% |

6% |

8% (underground mine) |

|

Corporate income tax |

25% |

30% |

30% |

30% |

30% |

30% |

0% on concentrate, 30% on tolling and refining profits |

|

Windfall tax |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

|

Variable profit tax |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Capital allowance |

100% |

25% |

100% |

100% |

25% |

25% |

25% |

|

Export duty on concentrate |

0% |

0% |

0% |

10% |

10% |

10% |

10% |

|

Sources: Manley, D. (2013) A guide to mining taxation in Zambia, Manley, D (2012) Caught in a trap: Zambia's mineral tax reforms, EY (2014) Global Tax Alert, KPMG 2014 Budget Highlights, IndexMundi and author's calculations. |

|||||||

The two main contenders for the office vacated in October upon the death of President Michael Sata appear to diverge on their views of these reforms. Edgar Lungu, from the ruling party the Patriotic Front, had previously vowed to maintain the current government's policy stance, though he has said recently that "nothing is cast in stone." In contrast the often pro-business Hakainde Hichilema (known as "HH") of the opposition United Party for National Development has likened the government's move to "a dairy farmer who milks his dairy cow until blood comes out and hopes to have milk the following day," suggesting that the government expects too much from taxing the companies so highly. Some analysts think that since the next president will have to run for re-election in 2016, any new government will be tempted to take a populist stance—i.e., maintaining the new regime.

On the back of all this are the growing budgetary problems which led the government to request IMF help in June last year. Zambia's weak macro-financial position will be a major challenge for the next president. If copper prices continue to fall, the government may face intensifying pressure from the industry to cut its high royalty rates, but will do so at a time when government revenues are under stress.

If the new government does decide to maintain the changes made in December, what might be the implications for Zambians? A preliminary analysis follows.

A little easier to administer...

Tax abuse in the mining sector has been a significant issue in Zambia for many years, thus it appears a key rationale driving the reforms was to ensure that tax revenue can actually be collected. Dropping the profit basis of corporate income tax on ore production and the variable profit tax should make the Zambia Revenue Authority's (ZRA) administration of the tax regime somewhat easier. This is because monitoring royalty payments only requires measuring the price of copper and the amount that each mine produces. This is not an easy task, as evidenced by the large sums that ZRA has said it is losing from insufficient monitoring of mineral exports, but it does sidestep the need to monitor mining costs, which is typically very difficult to do.

But perhaps hurting companies' bottom lines ...

Because royalties must be paid even when a company does not make a profit, the new rules might push companies to stop operations to avoid losing money. The companies have threatened closure and cessation of expansion projects, with Barrick Gold already initiating closure procedures on its Lumwana mine (which faces the 20 percent royalty rate). The Zambian mining industry association has claimed that the reforms will cost the country $1 billion in export earnings and 12,000 jobs this year. (Neither the government nor civil society organizations have come out with any alternative figures.)

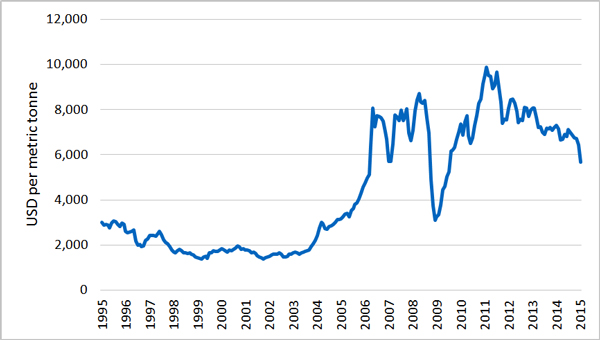

While industry threats have accompanied almost every tax reform Zambian governments have made in the past, this time they appear more credible. As the graph below shows, the copper price has fallen to $5,600, which is below the break-even line for the world's most marginal copper projects. IMF experts also think that some of the high-cost mines will close. This comes amidst a bitter dispute in which the Zambian government is withholding $600 million in VAT refunds from the mining companies. This is not to say that the new tax regime has gone too far in this respect, but the government may be making a rather poorly timed gamble given the current price of copper.

Source: IndexMundi

And difficult to tax super-normal profits in the future...

As the graph shows, changes in the copper price are nothing new. While it is not clear when copper prices will rise again, this possibility should be on the mind of any forward-thinking decision maker in Zambia. Unfortunately, without the corporate income tax and particularly without the variable profit tax, the tax regime has no mechanism to capture a share of the super-profits that the mining companies will likely make if the price rises again. While revenue from royalties will of course rise when prices do, revenue from the two profit-based taxes would be even higher. Any failure to capture this higher amount may have severe political consequences, as has been the case in the past. Mining dominates the political discourse in Zambia; when the copper price rises, citizens expect the government to collect more revenues. People may demand further reforms in the future, while creditors may be more willing to lend to the government if they know higher tax revenues lie ahead.

What happens next?

It's not clear whether the negatives of the new tax regime outweigh the positives. First, the higher royalty rates may indeed be too high for some mines, particularly some open-pit mines, to operate. The government may find that the losses in production and employment may not be worth the higher royalty payments from those mines that remain. But low-cost mines will continue to operate so the country will still earned tax revenues. Second, without corporate income and variable profit taxes, it will be difficult to capture super-normal profits in the future. However, the strength of these tax types rests on the ZRA's ability to administer them properly.

Civil society in Zambia also has a role to play by examining the impacts of the tax reform and advocating for improvements. For instance, the most recent Zambia EITI report provides some of the data, while growing work in open data and open modeling is providing civil society analysts with the tools necessary to undertake analyses of Zambia's mining tax issues.

It is unclear what the next president will do, but the international copper markets and Zambia's weak macro-financial position will be strong influences on his choices.

David Manley is an economic analyst at NRGI.

Authors

David Manley

Lead Economic Analyst – Energy Transition